This Labor Day, we are coming together to celebrate our past and all the Labor movement has provided, as well as consider our future and how all that we’ve fought for and won is being threatened by those behind the so-called Right to Work attack. Starting today and for the rest of the week, SEIU 721 will be bringing you powerful accounts from your fellow 721 members as they share how Unions have made an impact on their lives and on social issues. Your voice is invaluable, so please add to our conversation by reading the series and letting us know in the comments how you can relate. Also, share your labor movement stories on your social media pages and tell others how unions have made a difference in your life. Share your union pride on social media using hashtags: #LaborDay, #Union, and #FightFor15 The more people that can hear from us on social media the better.

This Labor Day, we are coming together to celebrate our past and all the Labor movement has provided, as well as consider our future and how all that we’ve fought for and won is being threatened by those behind the so-called Right to Work attack. Starting today and for the rest of the week, SEIU 721 will be bringing you powerful accounts from your fellow 721 members as they share how Unions have made an impact on their lives and on social issues. Your voice is invaluable, so please add to our conversation by reading the series and letting us know in the comments how you can relate. Also, share your labor movement stories on your social media pages and tell others how unions have made a difference in your life. Share your union pride on social media using hashtags: #LaborDay, #Union, and #FightFor15 The more people that can hear from us on social media the better.

Today and every day, let’s stand united to remind everyone that #AmericaNeedsUnions!

LABOR DAY: Birthed in blood, the battle continues

With all the emphasis on sales, back to school preparation and summer’s last hurrah, it’s easy to think Labor Day is just about rest and relaxation, but it wasn’t then and it certainly isn’t now.

That’s because the origins of the national holiday celebrating American workers didn’t start off with barbeques.

It started off with blood.

That Was Then

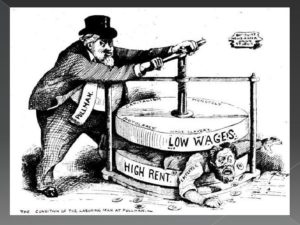

It all began with a strike at the Pullman Palace Car Company in Chicago.

The year was 1894 and the railroad car manufacturer had cut the already low wages of its workers by about 25 percent due to the economic depression that started a year earlier. However, housing costs in Pullman, IL, (which were controlled by and automatically paid to the Pullman Company) were

not reduced along with wages, and many workers and their families faced starvation as a result.

Upset over the declining wages, poor working conditions and 16-hour workdays at the factory, the workers tried to negotiate a solution with the company. But their boss, company president George Pullman, refused to meet with them.

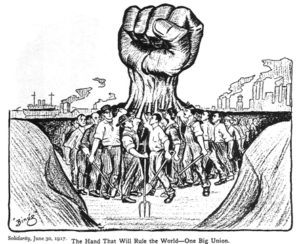

Workers appealed to the American Railway Union (ARU) to support them in talks with Pullman, but instead of arbitrating, he ordered the workforce to be fired. The delegation then voted to strike, and workers walked off the job on May 11, 1894. About a month later, ARU gave notice that its members would stop working on trains that included Pullman cars.

Fast-forward to June 30, and a whopping 125,000 workers on 29 railroads had quit work rather than handle Pullman cars. The boycott soon crippled railroad traffic nationwide, including mail delivery. Using the delayed mail system as an excuse, President Grover Cleveland declared the strike illegal and sent 12,000 troops to break it on July 3.

The strikers were furious by the introduction of troops and on July 4, workers and their sympathizers overturned railcars and erected barricades to prevent troops from reaching the yards. With a federal injunction preventing them from communicating with the workers, ARU leaders’ hands were tied, and on July 6 some 6,000 rioters destroyed hundreds of railcars in the South Chicago Panhandle yards.

The next day fights broke out between the troops and the workers.

National guardsmen fired into a mob, killing between 4 and 30 people and wounding many others.

It marked a bloody end to the strike. The federal troops were recalled on July 20 and the Pullman Company agreed to rehire the striking workers on one condition: that they sign pledges to never join a union. By the time it was all over, railroads had lost millions in revenue and in looted and damaged property, strikers had lost more than $1 million in wages and as many as 30 people had lost their lives.

Nervous about the political fallout from his heavy handed anti-union stance during the Pullman strike, President Cleveland made reconciling with labor forces a top priority. Several states had already been celebrating Labor Day but Congress rushed legislation to make it a federal holiday and it passed unanimously on June 28, 1894, a mere six days after the end of the Pullman strike.

Since then, the first Monday in September is “dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers. It constitutes a yearly national tribute to the contributions workers have made to the strength, prosperity, and well-being of our country.”

This is Now

The origins of Labor Day aren’t pretty, but it’s a fitting reminder that workers have ALWAYS had to fight, and the same is most certainly true today.

The so-called “Right to Work” movement is really “Right to Work for Less” and it’s an attack that’s been around since 1936. Just like Pullman so many years ago, management is still fighting to take away workers’ right to unionize,and already, 28 states have passed RTW laws.

Workers in“Right to Work”states have less workplace safety, are less likely to have health insurance, work for lower wages, and don’t have the ability to bargain collectively for fair contracts.

Just like with the Pullman situation, big anti-union forces are behind the attack. Back then it was George Pullman and his allies. Today it’s people like the Koch Brothers, the Freedom Foundation, and their greedy cohorts.

But just like the strikers did back then, we don’t have to sit back and take it. We can stand up. We can fight back. We are making our voices heard.

Rise & Resist.

History of Labor Day – History Channel Video (4 min)

___

Sources:

Northern Illinois University Library

___

In tomorrow’s “Voices of Labor Day” entry, read about E-board member Simboa Wright’s experience with the 1984 Olympics and how union jobs are key as Los Angeles prepares to host the 2028 games.

Share

Share

Share

Share