The life of John Lewis is a testament to the power of perseverance. His humble beginnings did not suggest that he would inspire millions to move mountains and overcome tremendous obstacles on the road to greatness. Yet that precisely what he did, helping liberate millions from racial oppression and ultimately being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom from none other than President Barack Obama, America’s first Black Commander-in-Chief, who later signed a commemorative photo from his inauguration ceremony with the words: “Because of you, John. Barack Obama.”

When America laid John Lewis to rest this week, the Civil Rights and Labor Movement worlds lost a groundbreaker and America lost a hero because John Lewis’ American Dream was about more than material prosperity for himself. He made it his mission in life to open up possibilities for others, to motivate people to take action and – above all – to be motivated always by righteousness. Born on February 21, 1940 to the son of Alabama sharecroppers, Lewis knew from a very young age that he wanted to be a preacher. By his teens, he had transitioned from delivering sermons to the family’s chickens to preaching in public among the people – ultimately graduating from American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee as well as Fisk University, and becoming an ordained Baptist minister.

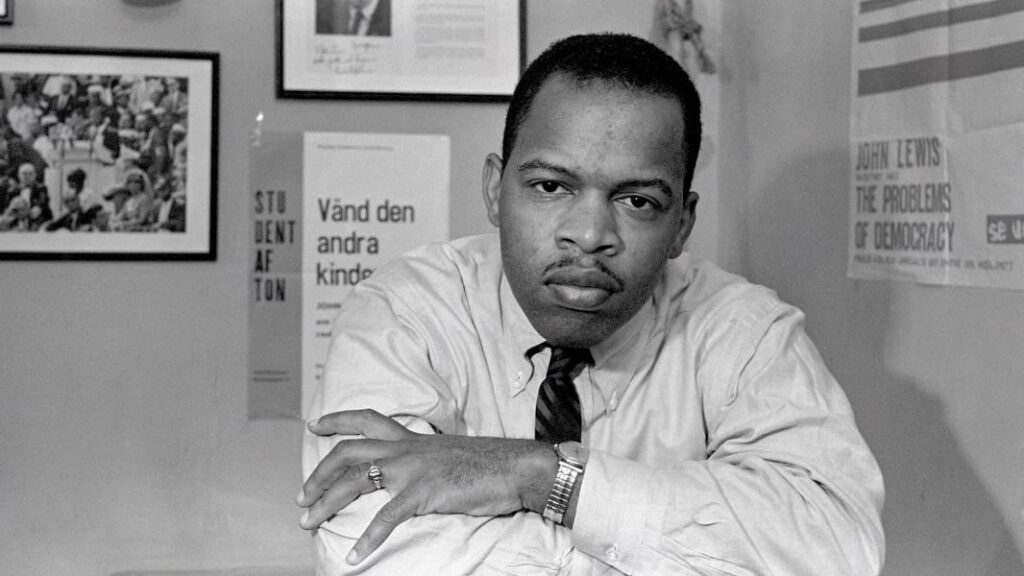

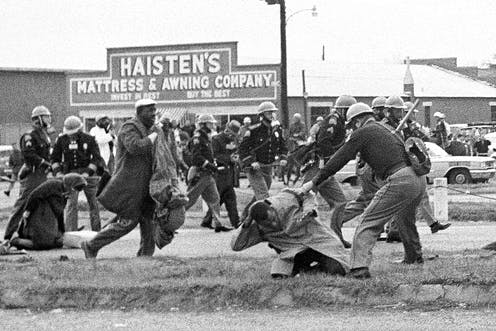

But he was about more than just talk. Seeking righteousness by fighting racism was the primary cause of his life and he put his life on the line many times for this cause all while doing so entirely through non-violent protest. In the early 1960s, Lewis organized numerous sit-ins at racially segregated Tennessee lunch counters and was one of the 13 original Freedom Riders. He endured incredibly vicious and violent assaults – literally spilling blood and nearly dying at the hands of both vigilante mobs and law enforcement. Lewis was frequently, and unjustly, arrested in states throughout the Deep South. By the time he started serving as Chairman of the legendary Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), he had been arrested 24 times – all due to his participation in non-violent protests for civil rights and racial equality. It was because of his leadership and organizing abilities that the SNCC made serious headlines and headway under his tenure – from opening Freedom Schools and initiating the Freedom Summer in Mississippi to organizing the Selma, Alabama voting rights campaign and participating as one of the “Big Six” leaders to organizing the historic March on Washington, which culminated in Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s momentous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Its vision of a Promised Land characterized by racial harmony and justice for all people remain the primary goal of Lewis’ work for the remainder of his long life. Well before the term “intersectionality” became popular, Lewis understood the connection between racial injustice and economic injustice. Yet he also knew that the Black community needed strong, dedicated voices and he rose to the challenge, intertwining this work with his involvement in interrelated causes. When Lewis headed the Voter Education Project in the late 1970s, the organization added nearly four million people of color to the voter rolls and when he worked for the Carter Administration running the VISTA program (now known as AmeriCorps VISTA), he focused his work on foster grandparents while ultimately becoming President Jimmy Carter’s Ambassador to the UN.

However, it was his career in public service as an elected official that made Lewis talked about once again at dinner tables across America. After serving on the Atlanta City Council for five years, he ran a successful, hard-fought campaign for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1986 – winning reelection 16 times. Lewis became known as the “Conscience of Congress,” fiercely defending Civil Rights and Labor Rights while also standing up for Gay Rights well before LGBTQ+ matters were taken seriously, let alone popularly accepted.

And while Lewis advocated for engaging in “good trouble, necessary trouble” to make the changes needed in society, he abhorred demagoguery and he did not shy away from calling out candidates seeking the highest office in the land – and more than one U.S. President who actually achieved the honor – from engaging in such behavior. Lewis was a determined man but he was a righteous one, too. He believed not in division but in reconciliation. Yet he also understood that in order to build a free and fair future we must first understand the institutionalized injustices of our past. Indeed, it is because of his perseverance that the Smithsonian Museum opened the National Museum of African American History and Culture adjacent to the Washington Memorial in 2016 – nearly 28 years after Lewis first introduced a bill in Congress to do so and always at the opposition of the notoriously racist Senator Jesse Helms.

When Lewis died on July 17, 2020, flags across the nation flew at half-mast to mourn a man who spent his entire lifetime fighting for the full dignity of all people. Dignitaries from around the world sent public condolences to pay their respects and three living former U.S. Presidents eulogized him. Especially given the volatility and uncertainty roiling America at this time in our nation’s history, may all of us who fight the good fight remember John Lewis as the definitive example to follow when making “good trouble” in the days ahead.

Share

Share

Share

Share